Political Capital, Part 1: Big Circles and Little Circles

Not everything that it's possible to do is permissible; not everything permissible is feasible. An obvious point? Yes, but complicated in practice.

As library leaders, we’re constantly faced with decisions that require an understanding of the boundaries that separate what’s possible from what isn’t – that define both what’s feasible and what’s allowed. (There’s merit, of course, in thinking about when and how one should try to transgress both of those boundaries, but we’ll address that idea in a later post.)

Here’s one of the most useful mental constructs I’ve found for thinking about the particular boundaries that define what is and isn’t allowed.

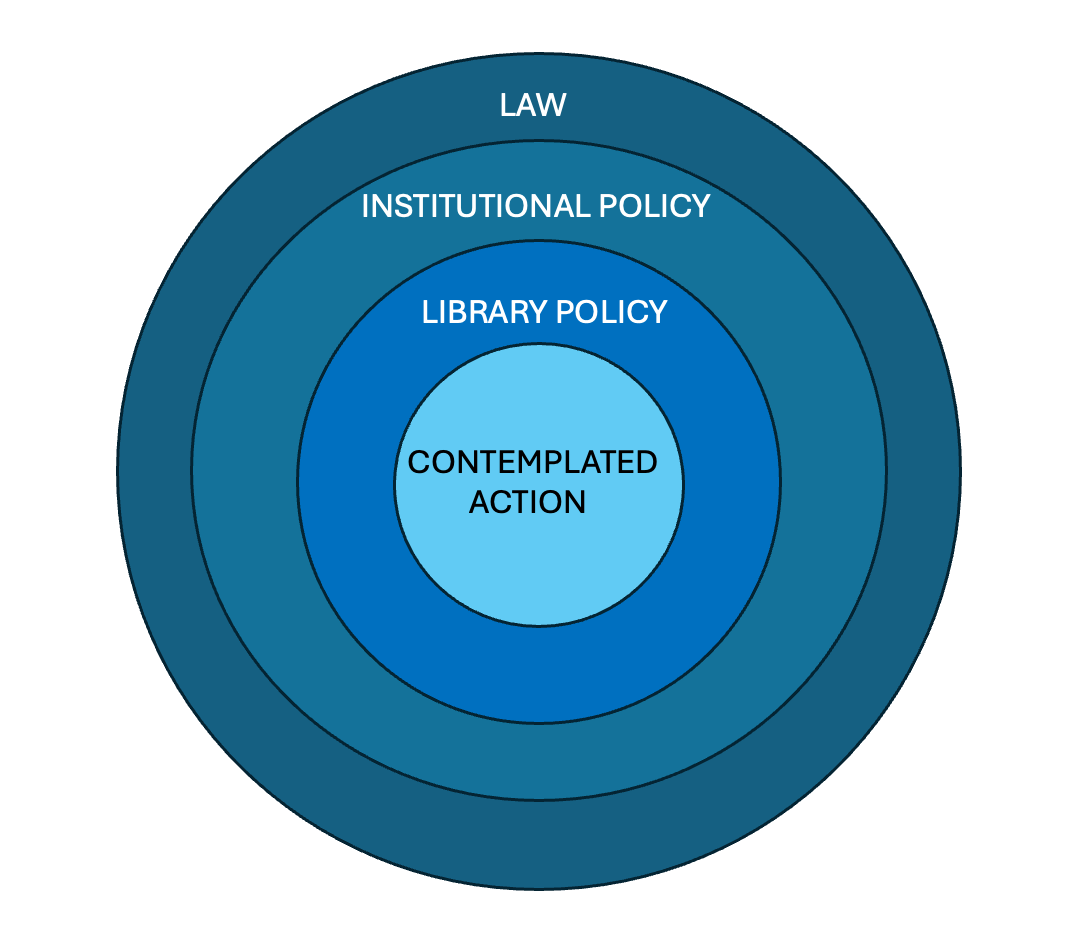

My staff have all gotten very used to – well, okay, maybe a little tired of – hearing me invoke the idea of “big circles and little circles.” In this model, concentric circles signify the scope of possible action. Understanding the parameters of these circles helps us avoid wasting time and energy debating options that aren’t actually on the table.

The construct is pretty simple, and for most of us it represents a principle that is intuitively obvious. Here’s how it looks:

What’s represented in this diagram is the simple fact that an institution’s practices are constrained by the law; a library’s practices are constrained by policies of the host institution; and individual library employees and organizational units are constrained by library policy. Each circle can move around within the next circle in the hierarchy, but doesn’t have authority to move outside the bounds of that next circle. In other words, while the library has significant room to make and adjust its own policies, it doesn’t have the power to enact policies that go against university policy – and doing so runs the risk of sanction.

So, for example:

Suppose a library department wants to extend a remote work option to its employees. The work of the department is such that doing it from home is reasonably practical, and there are lots of ways in which offering remote work would make life easier for the employees. The department head, finding that there is not currently a library policy regarding remote work, forwards a proposal to the library administration for consideration.

The library administration considers the pros and cons of the remote work proposal. The leadership group can see both significant upsides and real potential downsides to the proposal. Debate over letting the department offer remote work unfolds over the course of two meetings and several days of group email exchanges – issues of workplace equity, procedural efficiency, and patron service are all discussed, as are considerations of employee morale and the complex impacts that the department’s proposal could have in all of those areas. The conversation becomes not only time-consuming but also a bit heated. Feelings are strong on both the pro and con sides, and because the issues are complex, it becomes clear that there isn’t going to be a way forward that makes everyone happy.

Then one member of the administration puts her hand up and says “Wait. Is there a university policy regarding remote work?”. The group assigns someone to search the institutional policy library – and this person learns that, in fact, the university does not permit remote work except in unusual circumstances, which are tightly defined and do not include the circumstances at play in the library. With this, the group realizes that it could have spent its time and energy over the past few days on other issues rather than arguing the merits of a proposal that was outside the boundaries of the library’s authority to enact.

The principles at play here are, I suspect, pretty obvious to all readers: recognizing that libraries are subject to the policies of their host institutions isn’t exactly a deep insight into organizational dynamics. And yet I also suspect that any reader who has had experience as a manager or administrator is also thinking back to all the times that he or she had to discuss this very principle with one or more employees who wanted the library to enact a practice that contravened institutional policy, and who felt the library should “lead out” in this regard – or, at least, that the library leadership should advocate on behalf of their employees for a policy change to accommodate the proposed practice. And, of course, those employees may have been right.

To consider the more complicated dynamics of this situation, we have to think about the library leadership’s campus role in what we might call a “meniscus function.” And this brings us firmly into the realm of political capital, and its management.

We'll dive more deeply into this topic in Thursday's subscribers-only post.